To paraphrase Gygax, "character background is the first three levels" and in the same spirit, alignment is what you do with your character. Player alignment. Not the semi-jokey kind of schemes that lay out how players tend to behave towards each other, the GM and the game structure. One of those appears below.

By now several of these sectors are as mythical as the catoblepas (has anyone ever actually seen a "scenery-chewing thespian" player?) but this will do to illustrate what I am not talking about. I am talking about observations made over the years as to how players, when not constrained by alignment, tend to play their characters. Player-determined alignment is real but, going beyond what I wrote several years ago, it doesn't correspond to any alignment scheme used in D&D or in the most fervid, hair-splitting heartbreaker. It's a characterology all its own, that deserves its own terms, put together in opposing pairs.

Impulsive: The player can't stand boredom and pushes the character to propose reckless plans, start fights, and generally see what they can get away with. Their action will usually account for half the party's failures and half their successes.

Impulsive: The player can't stand boredom and pushes the character to propose reckless plans, start fights, and generally see what they can get away with. Their action will usually account for half the party's failures and half their successes.Strategic: One kind of leadership role, this player moves very cautiously, often is found physically restraining other characters, and wants time to think things through. Not a rules lawyer, but the most likely to consider the rules as part of the plan.

Exuberant: Another kind of leadership role, the player runs the character as a striding, swaggering bag of charm; not so much reckless as eager to please the crowd with the best move, the best solution. The crowd, by the way, includes the GM.

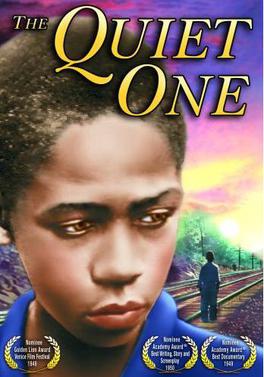

Exuberant: Another kind of leadership role, the player runs the character as a striding, swaggering bag of charm; not so much reckless as eager to please the crowd with the best move, the best solution. The crowd, by the way, includes the GM.Quiet: This player may be introverted, unsure, or just enjoys watching the game play out around them. They respond when spoken to, are often asked to run point or guard the rear or cast a spell, but rarely propose anything on their own. There is a lot of middling GMing advice written about trying to draw this player out but I find that acknowledging their existence in small and meaningful ways works best.

Dark: This player, through their character, expects the worst of what's around them, and so feels justified in doing the second-worst. This can take many forms and is not always the stereotypical dark elf assassin, but distrust, avoidance and sneak attack form part of their usual counsel to the rest.

Naive: The player enjoys portraying an overly trusting person, whether a fool or just really kind-hearted, to lighten up the grim, heavy, paranoid world of adventure. They're such a perfect patsy for the usual DM array of sympathy traps that you almost feel bad springing them on such an obvious mark.

Obsessive: What the "thespian" stereotype gets wrong is that real acting is hard, ham acting is self-policing, and usually players who want to play their character to the hilt open up a can of spam based on one obsession, be it food, wealth, combat, sex, religion, or hate. They use it more as a running gag than an excuse for soliloquies. Really, there's enough irony in the water these days that if the room isn't laughing heartily, they'll turn off the shtick real quick.

Eccentric: Kind of the mirror twin of the obsessive but coming from an opposite place, this character sends out a lot of random signals but there's a difference between playing weirdo and playing impulsive - the impulsive player is trying to accomplish something and sometimes succeeds but the eccentric is just trying to make a style point, like Nerval walking a lobster. Truth be told, though, frame-breaking jokes are so common among everyone that this one's "wacky" in-character pronouncements get mistaken for out-of-character banter half the time. White Wolf did a good job of writing niches for this kind of player into their games.

So with this scheme in mind, there's really no reason to write it on the character sheet, because it's what the player does. But for a GM, rolling a d8 or two to come up with personality elements for an NPC that's easy to play because you have the examples all around you - that's another matter.