In

writing adventure material, nothing pays off like primary research. Look into

the lives of rats, and you find that they are purblind and communicate

subvocally. Pay attention to stone, and you find that at the juncture of

limestone and granite sometimes grows a layer called skarn, laced with gold,

copper, and gems. Architecture, chemistry, botany: as much as they constrain

design with realism, they also open up intriguing possibilities with the ring

of reality to them.

Lack of

research also shows. How many lost mines, dwarven or not, have been written up

for adventures? How many of them have been glommed together from the residue of

Moria-sublime (halls, chasms, demons) and Wild-West-banal (railcarts, lifts,

ingots)? The one thing that's certain is that horrible things from the deep

have been unleashed and are now running around in the place. But can we do

better in setting the scene?

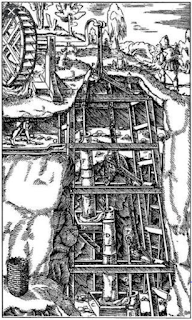

|

| Waterwheel-driven pump |

Even

cursory research turns up one detail of deep metal mining, in medieval Europe

or any other civilization, that presents enormous challenges. Below the water

table, mines tend to flood. The simplest solution: dig a drainage channel, or

adit, to lower ground. But this presumes your mine sits on higher ground from

somewhere. Deep mines don't have this luxury.

So, pump

the water out. At first people pass buckets hand to hand, then as craft

deepens, machines use hand power, mule power, water power to lift out the

groundwater using buckets, screws, suction pipes and tubes. All these latter

solutions need keeping up, and once the mine is abandoned, the lower levels

partly or fully fill with water.

Flooded

floors, concealing pits and swimming monsters; flooded tunnels, requiring magic

light and water breathing to have any chance of mere survival. Or, another way:

get the old pumping machinery working again and see how much you can clear out,

and what treasures lie in the murk.

All this

assumes a pre-industrial European level of technology. But a fantasy world also

has dwarves, that people of notably precocious craft. Indeed, one solution only

they might reach comes from the computer construction game Dwarf Fortress,

whose worldbuilding is as complex as its graphics are crude. The game simulates

groundwater by having some settlements sit over an aquifer level, whose water floods and ruins

all construction beneath it. The way past the aquifer requires one of many

complicated engineering solutions, including rapid pumping, opening a shaft to

cold air that will freeze the water, or dropping a "plug" of dry

stone into the wet level and boring through it.

|

| Dropping the "plug" |

Although Dwarf

Fortress simplifies the geological reality of seepage, the plug idea suggests

that dwarves might have the skill to locate the source of groundwater and

simply wall it off with non-porous stone. Maybe the water is controlled and

channeled into a reservoir, for drinking and industrial use.

Allow a

certain amount of magic in mining, and the pumping operation can be helped in a

dozen ways. Maybe the dwarven priests have deals with elementals, or maybe

these solutions are found among other underground peoples, like the dark elves.

Golems can be set the task of working the pumps. The miners themselves breathe

water in flooded galleries. Magic freezes flooded caverns so that ice tunnels

can be dug through. A portable hole, or elemental portal, does the work of an

adit in draining off water. And what might come through the portal the wrong

way?

Another

difference: human metal production historically had to be distributed over

several sites, because the material for processing ore -- water, wood, and

aboveground oxygen -- was not present within a mine, and not necessarily

plentiful close to it. Dwarves, though, live entirely underground. Their mine

dungeons necessarily include areas for crushing ore, then sorting and filtering

the metal-bearing compounds through the action of water. They need to smelt ore

in the heat of a furnace, creating liquid metal. If steel is being made, the

fuel needs to infuse the raw iron with carbon. Most likely for dwarves this

will be mineral coal rather than the medieval-era charcoal. Why not have the

facilities for shaping and working metal objects right there to hand as well? A

whole complex suggests itself. The only limit is availability of fresh air and

water, which architecture or elementals need to supply. And Dwarf Fortress

gives another idea: using the earth's own magma to power fierce furnaces.

In short,

thinking about realistic logistics can take you places in design your

unconstrained imagination never would. It can insert unforeseen challenges into

mundane mines, or underwrite the need for a thematically varied industrial site

in the more fantastic variety.